2 min read

Gospel-Centered from the Start

“Let us hold unswervingly to the hope we profess, for He Who promised is faithful…Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.” (Hebrews...

6 min read

Barbara Comito, former marketing director

:

December 19, 2013

Barbara Comito, former marketing director

:

December 19, 2013

By Barbara Comito, UGM Staff Writer

I met Sammy and Ambre in Freeway Park (a mere plot of grass and trees in the midst of the concrete and pavement under I-90) when I was doing a story for the Mission News. Ambre was approachable, her body language relaxed, open. She seemed lonely and almost childlike as she sat in the park surrounded by all her worldly possessions – a sleeping bag, a tent, a backpack and a few clothes mixed together with stickers, markers and a few simple drawings.

Soon after I sat down, she pulled out a well-worn picture of her three little girls. As she told me the story of losing them to Child Protective Services, I thought of my own children, and I empathized with her desire to escape what must be unbearable pain.

Sammy rode up on his bicycle – agitated, wary – Who was I? What did I want? He couldn’t sit still. He rolled a cigarette, smoked it, gave Ambre a puff, got up, walked off, came back and stopped Ambre mid-sentence when he thought she was telling too much to a stranger.

“There’s a story behind someone walking around with their whole life on their back.”

Ambre, however, desperately wanted someone to listen, to understand. “People look right through us like we’re not even here…You have to remember there’s more behind the backpack or the shopping cart. There’s a story behind someone walking around with their whole life on their back.” I pulled out a couple water bottles and granola bars and listened.

Ambre started running away when she was 12. Her father, she said, abused her and arranged for her to be molested by other men. She went to live with her mom when she was 15. Sammy is more than 10 years older than she is. He has bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, paranoid tendencies, she said, but he takes care of her.

I sat there with Ambre for close to an hour, even though Sammy was clearly uncomfortable. “I don’t know you,” he kept saying, and yet, he genuinely seemed to care for Ambre and wanted her to have another woman to talk to.

“Do you really want to hear all these bad things?” Sammy asked. “We used to be happy.”

I asked the two of them how they survived day in and day out.

“We utilize the people who feed people,” Ambre said. “We don’t stay in shelters because they don’t have a man and woman shelter where we can stay together. We refuse. They’ve already taken everything from us, and we refuse to let them separate us, too. We’re all each other’s got.”

They use the restrooms at fast-food restaurants downtown. They panhandle and scrounge until they can save up enough money for a motel for a night. Sometimes Ambre showers at the Women’s Hearth. They warm up over coffee at City Gate.

"We're soldiers."

“We’re soldiers,” Sammy said. “I was born into this.” Ambre interjects that he was born prematurely to a heroin-addicted prostitute. “But I rose above that,” Sammy said proudly. “The two of us are fairly intelligent people as far as I can tell. We stay alive – not very easy to do out here.”

“It’s hard out here,” Ambre added. “And you know what? People get ripped off. People get screwed over, and people get mad about it. We sleep in a different spot every night because we’re not gonna let somebody…” Sammy interrupts, “Hit us in the head or something.”

Ambre spreads her arms to indicate the space around her. “We have these two sleeping bags. I have one pair of jeans that are dirty. I don’t do laundry. When my clothes are dirty, I get rid of them. I get clothes from the donation box at the Goodwill…whatever. I’m not gonna lie. That’s one of my favorite clothing stores – the drop box behind the Goodwill. We have no income.”

Both Sammy and Ambre were extremely worried about being outside during the winter.

“It’s getting cold fast. It’s already cold at night, definitely cold. I have severe health problems. I’m an asthmatic. I was hospitalized four or five times this last winter. I had pneumonia in May. And it’s starting to get cold at night. We really want to get our [stuff] together.”

Sammy and Ambre told me they had a chance to get off the streets. All they needed was $200. They’d found a landlord who would let them move in for just $200. Sammy had a lead on a job. He had been a manager at Burger King, and they would let him come back if he was clean. He could get clean, he said, if he could just get off the streets.

“If we had a stable place to wake up every day,”Ambre said, “he’d have a job in an instant. Give him a couple days to clean out. The only reason we stay doing dope is because we’re on the street.”

I believed them. I liked them. They did seem intelligent, articulate. And life seemed to have dealt them some hard blows. I thought they deserved a chance. I gave them my number and the number of my church. And when I went home, I talked to my husband. I told him I wanted to help them. He said OK, so I drove Sammy and Ambre over to the apartment complex they had heard about.

"If we had a stable place to wake up every day, he'd have a job in an instant."

“The apartment” turned out to be nothing more than a room, like an office, with no windows, no furniture, no bathroom, no running water – just a room with dirty carpet and access to a bathroom and kitchen on the same floor. Still, it seemed better than the street, so I wrote the check for $200 to the landlord and left an ecstatic Sammy and Ambre to move in, promising to bring food later.

Less than 24 hours later, I got a call from Sammy and Ambre that the fire department was closing down the building, and they had to get out that same day. They were in a panic. Now where were they going to go?

I had no idea, but I also knew that I was committed. I couldn’t just turn my back or throw up my hands. After I got off work, I went to pick them up and looked in amazement at what they had acquired in one day – a mattress, a TV, boxes of food– all stuff they left behind. After a considerable search, I found the property manager and got my check back. Then, I loaded Sammy, Ambre and their stuff into my mini-van and took them to dinner.

Again, Sammy had trouble sitting still, and I had a feeling he was high. He ordered but didn’t eat, and Ambre, with her meth-riddled teeth, picked at her food. Every option we explored for temporary housing turned out to be a dead end. I even drove them to a campground in Spokane Valley, but it was isolated, and without a car, I couldn't see how they could get food. In the end, I took Sammy and Ambre home with me.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a saint. I wasn’t brave and courageous. I was afraid. I had teenage children at home. Sammy and Ambre stayed in a tent set up on my deck. I bought cigarettes for the first time in my life to keep Sammy from bumming them off the neighbors. My husband, a chef, fed them great meals that took Ambre’s sore teeth into consideration. We took them to church on Sunday morning, and I explained their situation to the congregation. The guest pastor gifted his speaking honorarium to their housing fund, and on Monday, they found a place – an actual apartment – that would let them move in for $400.

I brought them a box of food, and I prayed. Prayed that they would make it. They didn’t. Sammy didn’t get his job at Burger King. They didn’t stay clean, and they were evicted.

I stayed in touch with Sammy and Ambre off and on over the next few months. I bought groceries for the family of six who let them sleep on their living room floor. I answered Ambre’s pleas for help when she said Sammy was abusing her and offered to take her to the Crisis Shelter. She wouldn’t go. In the end, I told them I couldn’t be their food bank. They needed to find other resources. In a few short months, they had exhausted my patience.

The last time I saw Sammy was on the street downtown. He said Ambre had left him.

Postlude: Granted, this story doesn’t have a happy ending, but if I had it to do over, I’m not sure I would have done anything differently. It hasn’t made me hard. Neither, I'm afraid, has it made me any wiser. On the one hand, I didn’t suffer any repercussions for my lack of prudence. On the other hand, I’m not sure anything was gained in terms of Sammy and Ambre’s situation. I don’t know if their rather negative perceptions of God and Christians were changed even a little.

I have not told this story here in order to say, "Do this" or "Never do this." I have told this story to illustrate that homelessness is a complicated problem and only peripherally related to whether or not a person has or doesn’t have a “home.” It is so much bigger than that.

This is part of a multiple-post series on How to Help the Homeless first published in 2013.

To find more ways you can help, download this e-book with all our ideas in one place.

The Face of Homelessness:

This was Part 2 of a series. Part 1 focused on the magnitude of the problem. Part 3 has a surprising piece of advice from Executive Director Phil Altmeyer. Part 4 introduces UGM's 3-part approach to breaking the cycle: Rescue, Recovery and Restoration.

2 min read

“Let us hold unswervingly to the hope we profess, for He Who promised is faithful…Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.” (Hebrews...

9 min read

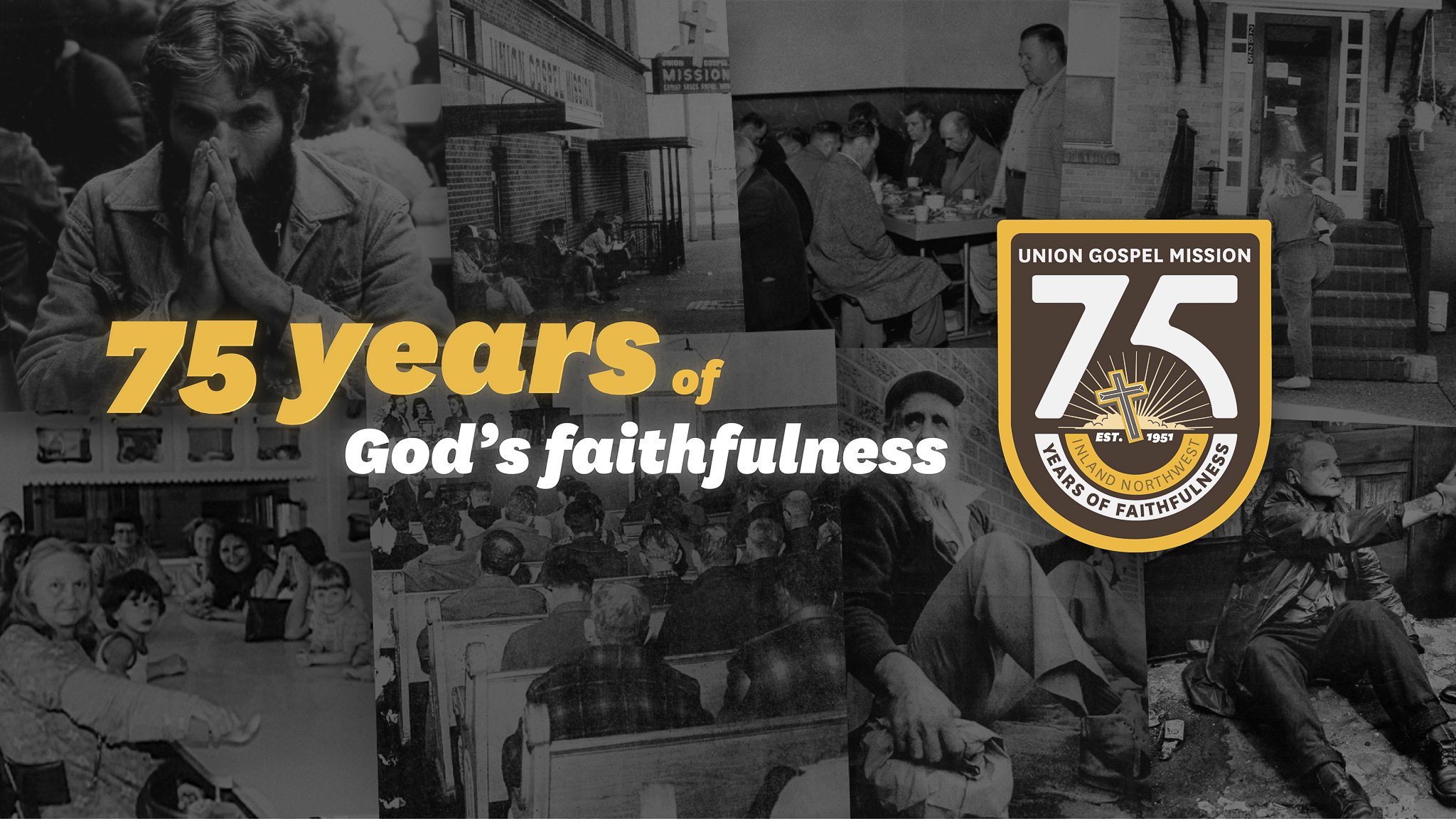

To celebrate 75 years of serving the Inland Northwest, we are spending the year remembering our history and the faithfulness that built us and...

2 min read

In 2026, Union Gospel Mission Inland Northwest is approaching our 75th Anniversary! This is a milestone that invites gratitude and reflection, and...

The Spokane Police Department is piloting a new approach to dealing with homeless encampments. The idea is to clean up the camps while also offering...

“I was brought up in a family of musicians and my dad was the smartest man I’ve ever known, a philosopher.” Johanna is well spoken, educated and...

1 min read

In her article “Does Poverty Cause Homelessness?” Marchauna Rodgers argued that the United States has misdiagnosed the problem of homelessness,...