2 min read

Gospel-Centered from the Start

“Let us hold unswervingly to the hope we profess, for He Who promised is faithful…Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.” (Hebrews...

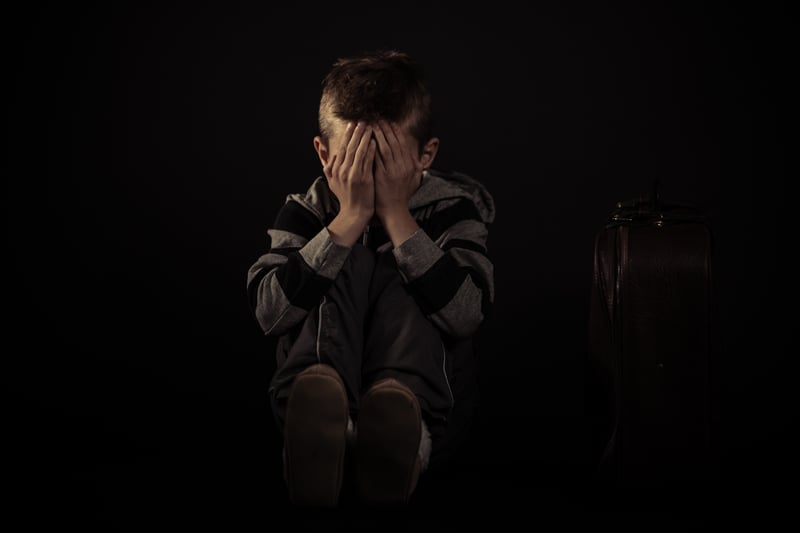

This month on the Impact Blog, we’re looking at issues of the mind: sadness, depression, anxiety, mental illness, darkness vs. light. There’s a wide spectrum of struggles there, and we’re tapping UGM’s experts to provide helpful explanations – and hope! – for people who struggle with these on an ongoing basis. Here, John looks at how childhood trauma continues to affect victims in adulthood, and why LIFE Recovery takes a long-term approach to helping them.

By John Dunne, former UGM Men’s Recovery counselor

Jack is in his late thirties, and he is homeless. He enters our recovery program asking for help, saying that he now admits he is addicted to alcohol and opiates and is willing to do whatever it takes to stop his life-threatening addiction and find a new way of life.

What do you think Jack needs in a program so he can experience life change? If you say he needs addiction recovery in a Christian environment, you have correctly described the first phase of our 16-month residential program.

Now let me tell you a little more about Jack's history, and keep in mind that this information will normally trickle out of a client over a number of months as he gradually learns to trust the program staff and his counselor.

Jack's father was a drug addict. He alternately abused his children and overindulged them. Jack's mother was very codependent, and after divorcing her abusive husband when Jack was 6, she had a series of live-in boyfriends and husbands. Jack was sexually abused by one of those live-in boyfriends from the ages of seven to nine. When he was 11, he stole some of his stepfather’s drug money to buy food and was beaten so severely that he stayed home from school for a week and a half so the bruises would heal.

Jack saw his mother beaten on a regular basis. He hid in his room when he was small, and when he was 10 and older he tried to protect her.

Jack saw his mother beaten on a regular basis. He hid in his room when he was small, and when he was 10 and older he tried to protect her.

Jack was diagnosed with ADHD in fourth grade and was placed in special education classes because he could not focus on school work. He was teased by the other children because his clothes came from Goodwill. He was expelled numerous times for fighting, started smoking marijuana in junior high, and dropped out of school altogether at fifteen. One stepdad screamed at him and cuffed him in the back of the head when Jack couldn’t get his math homework problems right, so he has never attempted to get his G.E.D. because of test anxiety.

Jack's adult life has followed the same script as his childhood because it was the only script he knew. Like a well-structured play, all of Jack's jobs, careers, relationships and marriages had a beginning, a middle, and an end—emphasis on end. Nothing lasts.

Life is a survival task for Jack, and he is good at surviving. Like a concentration camp survivor, he lives his life in hyper-vigilance mode, making all of his decisions with the part of the brain that reacts to life-threatening circumstances. The limbic system is that survival part of the brain, and it gives us only three choices: fight, flight, freeze. Because this part of the brain activates the adrenal glands to produce overdoses of adrenaline, Jack needs depressant drugs like alcohol and pills to calm his hyper-aroused system.

Michael Dye, an expert in addiction recovery whose book forms the basis for much of the material in phases two and three of our program, says all addictions have a specific purpose: They help us block out uncomfortable thoughts, feelings and memories. Jack has a lifetime of these unbearable thoughts, feelings and memories, both from what he has experienced as a victim and from what he has perpetrated on others. He has kept all of this pain and guilt buried inside him like a house that has human corpses rotting in the cellar. Jack lives on the main floor, where he uses drugs and alcohol like deodorizers and perfume, trying to keep the stench under control. In Jack's world of denial, drugs and alcohol have been the solution, not the problem.

If Jack only gets help for addiction recovery and not for trauma recovery, he will fail in life recovery for a number of reasons. Jack has poor health now. His immune system has been overwhelmed and distorted by the constant supply of adrenaline that the limbic system demands. His immune system does not have the strength to fight viral and bacterial infections, and it overreacts to minor irritants, creating allergy symptoms. His immune system is like a shell-shocked, wounded soldier who just starts randomly firing his gun at imagined enemies an does not target the real ones.

Jack will fail in job and career because he lacks a G.E.D. Any kind of educational environment triggers childhood memories of trauma and teasing, and he avoids these opportunities to better himself.

Jack will fail in relationships. He has been conditioned from infancy and childhood to bond with a mixture of love, abuse, and rejection. His mother loved him because he was her child, and she hated him because he was a little version of the man who abused her. Jack has only been able to deeply bond with women who are unrecovered sexual abuse victims and who speak the love-hate language that feels like home.

Jack will fail in relationships. He has been conditioned from infancy and childhood to bond with a mixture of love, abuse, and rejection. His mother loved him because he was her child, and she hated him because he was a little version of the man who abused her. Jack has only been able to deeply bond with women who are unrecovered sexual abuse victims and who speak the love-hate language that feels like home.

I hope this description of “Jack” explains a little of why we do what we do in our sixteen-month recovery program. To describe the actual techniques of counseling and therapy would take a book.

Let me summarize the process with a metaphor, one that is drawn from the Gospel of John. Lazarus has died, much like Jack the client started dying in his childhood and has pretty much lost any real quality of life in his late thirties. Only Jesus can resurrect a life from the tomb. But notice that after Jesus brings Lazarus to life again, he directs the community to “unbind him” from his mummy-like funeral wrappings.

Only Jesus can bring Jack back to life. He challenges us, invites us, and empowers us to unbind the paralyzing wrappings of old trauma and toxic memories that would still imprison our brothers and sisters.

John Dunne received his Master of Arts in Counseling from Whitworth University in 1998. He has a certification in Chemical Dependency Counseling from Spokane Falls Community College (1993), as well as a Master of Arts in English from Seattle University (1978). John worked as a counselor in the Men’s Recovery Program for more than 18 years and is certified as a relapse prevention specialist through Michael Dye CADC, NCAC II/Genesis Process.

Just like in Jack's story above, we all need to find our identity in Christ instead of the painful labels we've received from others. Remind yourself of your true identity with our beautiful printable bookmarks by clicking below.

2 min read

“Let us hold unswervingly to the hope we profess, for He Who promised is faithful…Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.” (Hebrews...

9 min read

To celebrate 75 years of serving the Inland Northwest, we are spending the year remembering our history and the faithfulness that built us and...

2 min read

In 2026, Union Gospel Mission Inland Northwest is approaching our 75th Anniversary! This is a milestone that invites gratitude and reflection, and...

.jpg)

My name is Guadalupe Granados. At 35 years of age, I feel like my life is just beginning. I’ve wasted so many years as a passive bystander,...

As we approach the Easter season, I feel gratitude for the Christian heritage that brings a deeper meaning to the season than Easter egg hunts,...

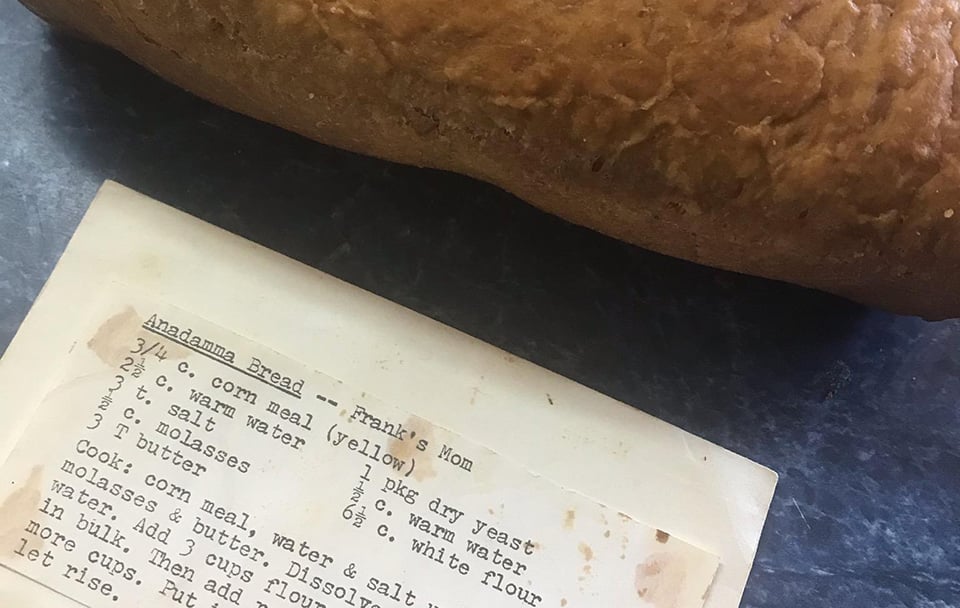

COVID-19 created some strange shortages – toilet paper being the first and most memorable. But bread was another, quickly followed by flour as people...