6 min read

I Was Once Where They Are

“Jesus had been with me through it all; I just didn’t have my eyes open."

Underneath homelessness, we often find addiction and, underneath addiction, trauma.

Trauma invades, wounds, hides and resurfaces, wreaking havoc again and again. Trauma breaks bonds, gives birth to shame and pulls a person into patterns of self-destruction. Trauma goes deep, so healing must go even deeper.

Homelessness doesn’t happen simply because someone loses a job or suffers a medical emergency. Homelessness happens because people who are deeply wounded do not have a solid, secure network of family and friends and churches to catch them when they fall.

The Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente conducted a study from 1995 to 1997 that found a direct correlation between childhood trauma (Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACEs) and damage to health and wellbeing later in life. The higher the number of traumatic incidents, the greater the likelihood of disease and self-destructive behavior.

Later, a study done by Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness found a direct correlation between ACEs and adult homelessness. The higher the ACEs score, the higher the likelihood the person would experience homelessness. A full third of the individuals with an ACEs score of 8 were homeless.

High ACEs scores also correspond with higher incidences of mental illness and substance abuse, and many of these negative outcomes are co-occurring.

In other words, children who are neglected, abused and abandoned, children whose sense of safety and security is critically compromised, grow up to have a host of other issues. The more trauma in childhood, the higher the level of dysfunction in adulthood.

The more trauma in childhood, the higher the level of dysfunction in adulthood.

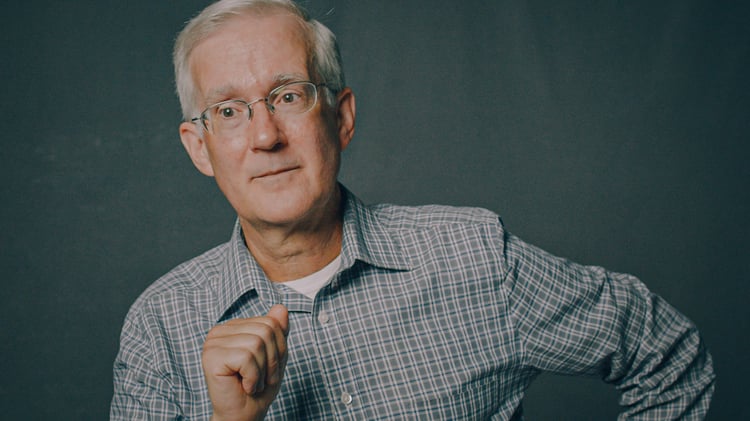

“This was one of the first studies that actually proved that early childhood events have this great effect on physical health, on homelessness, on abuse, on suicidality, and that it really does affect how one interacts with their body, with the outside world, and affects their likelihood to thrive.” – Dr. Mark Baird, Whitworth professor and clinical psychologist specializing in trauma.

“Childhood trauma teaches kids early on that life is dangerous. The very homes that are supposed to be havens of happiness and support, instead are war zones. Their internal alarm is constantly getting tripped, knocking their Cerebral Cortex off-line, inducing extreme feelings of terror, but leaving few resources to deal with those overwhelming feelings.

“Drugs and alcohol quiet that alarm and numb that terror. Sure, they have significant long-term consequences, but when we are operating in our limbic system, our Cerebral Cortex is off-line and we’re unable to think in the long-term.

“That’s why treating drug and alcohol addiction and homelessness isn’t just about changing the behavior. It’s about helping to quiet that alarm in healthy, life-giving ways.”

The ACEs study tells us that to break the cycle of homelessness and addiction, we must address the deep wounds left by trauma, wounds that affect the whole person – body, mind and soul. That kind of healing doesn’t happen in 30, 60 or 90 days. It takes intentionality, honesty and commitment, and it can only happen within the confines of a safe community.

Dr. John Wolfe, clinical neuropsychologist and certified trauma therapist, described the complexity of human nature: “God made us as spiritual beings created in His image, but we live in this fallen world. We are biological beings. God made us as people of flesh and blood and brains and neurological processes and physiological processes. But that biology lives out in a social world. We have relationships with other people. And then there’s our own psychological makeup – who we are, how God wired us with personalities and temperaments. And these collectively make up who we are at this moment in time in our journey through life.”

The biopsychosocial model, first proposed by George Engel and Jon Romano in 1977, is a way of looking at the interrelationship between the mind, body and spirit with regard to physical and mental health. It recognizes that the different parts of a person affect each other – what’s going on in the mind affects the body and vice versa.

And our whole selves – body, mind, spirit – are affected by trauma.

Dr. Wolfe explained that trauma shapes a person’s identity. People begin to view themselves differently and wonder, “What’s wrong with me?” They define themselves as damaged. Their view of the world is altered: no one can be trusted. “I have to be in control. I have to take care of myself.” Their life choices narrow. The people they choose to journey alongside tend to be people with similar struggles. And, unfortunately, they often become perpetrators of trauma which, in turn, compounds their own trauma. They experience moral trauma because they have violated their own consciences. They feel shame and are further convinced that, at their core, they are bad.

Robert Turner, who finished UGM Recovery last year, recognizes that his identity was deeply marred by trauma: “I had no concept of love. I didn’t believe I was worthy of love.” Over his time in program, he unearthed the root lie: “I’m a mistake. I’m unwanted. No one will ever love me, and this is what I deserve in life.”

Robert acted out of that identity and perpetuated the cycle of abuse. Having been sexually abused as a child, he associated sex and love in unhealthy ways. His primary addiction was sex. He worked as an erotic dancer, slept with his friends’ girlfriends, married women… “It didn’t matter…anything to try to feel wanted or loved. I hated myself. I used promiscuity and drugs to numb that away. It never worked.”

Becky Wall, a certified mental health therapist and former counselor at UGM, explained that we build our definition of ourselves from our primary caregivers and the signals they give. When the primary caregiver behaves shamefully, the child picks up the shame. He believes he is responsible, and it shapes his identity.

That sounds a bit hopeless, but it’s not.

New neuropathways can be developed. It takes time, but identity can be re-shaped. The thing is, it won’t happen in a vacuum or tucked away in an apartment by yourself.

“We change in community. People hurt you. It will be people who heal you,” Becky said.

Robert testifies to the truth of that statement, as well. His healing began when he told his story – all of it, what had happened to him and what he had done – to the men in his phase at UGM.

“The healing process really began with Genesis [a recovery class that delves into the roots of trauma]. I was the last person to share my life story, and I was throwing up in a trash can beforehand… It was the first time I’ve ever been honest, and I think that was the breakthr0ugh moment.”

Robert participated fully in the self-evaluation process. “You stand up in a room full of men who are also broken, who aren’t judging you. They have their own baggage.” It was through that process, Robert said, that he discovered he had a voice.

Robert spoke his truth. His counselor listened, and together, they prayed through everything.

“Yes, it happened. Yes, it was terrible, but it doesn’t have to control my life.”

Robert said his recovery has also been about accepting personal responsibility. “You have to grow up. You cannot hold onto that pain… I see the error of my ways, and I’m willing to put in the time and effort to change that.”

If he could speak to his younger self, Robert says he would tell him, “You have a Father who loves you. It can be different.” He grew up without his biological father; his mother was an addict, and his stepfather was abusive.

At UGM, gospel is the heart of recovery. We have all sinned. We are all broken. But when we confess our sins and accept Jesus as our Savior, we are forgiven. At that point, we are given a new identity as children of God. “God didn't wait for me to put on my Sunday best,” Robert said. In fact, Scripture tells us that He loved us while we still hated Him (Romans 5:7-8).

“Recovery,” Becky said, “is not just unraveling the past but discovery – discovery of who you were meant to be. It’s more than changing who you are. It’s going back to who you were created to be – returning back to your noble self.”

“Recovery is not just unraveling the past, but ... discovery of who you were meant to be.” -Becky Wall

Often that self-discovery begins with “seeing ourselves through the love of other people who care and nurture us. That’s the role of counselors and therapists,” Becky said.

And that’s the role of a safe and healing community – reflecting the love of God to people who have a hard time believing it. Being the hands and feet of Jesus, expressing His love.

Today, Robert says, “My whole idea about self-worth comes from who the Word of God says I am.”

See how God's love impacts UGM guests in this free e-book.

6 min read

“Jesus had been with me through it all; I just didn’t have my eyes open."

2 min read

“Let us hold unswervingly to the hope we profess, for He Who promised is faithful…Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.” (Hebrews...

9 min read

To celebrate 75 years of serving the Inland Northwest, we are spending the year remembering our history and the faithfulness that built us and...

“In the beginning, I thought I was free,” Rowan said, “and in the beginning, I thought he was going to be everything I ever wanted—he had a Mohawk,...

Written by Chrystin and read at the fall 2022 LIFE Recovery phase promotion at UGM's Center for Women and Children. Dear Monster,

Recovery is impossible... if you don’t believe you have a problem if you refuse to look at the problem if you blame someone else for the problem or ...